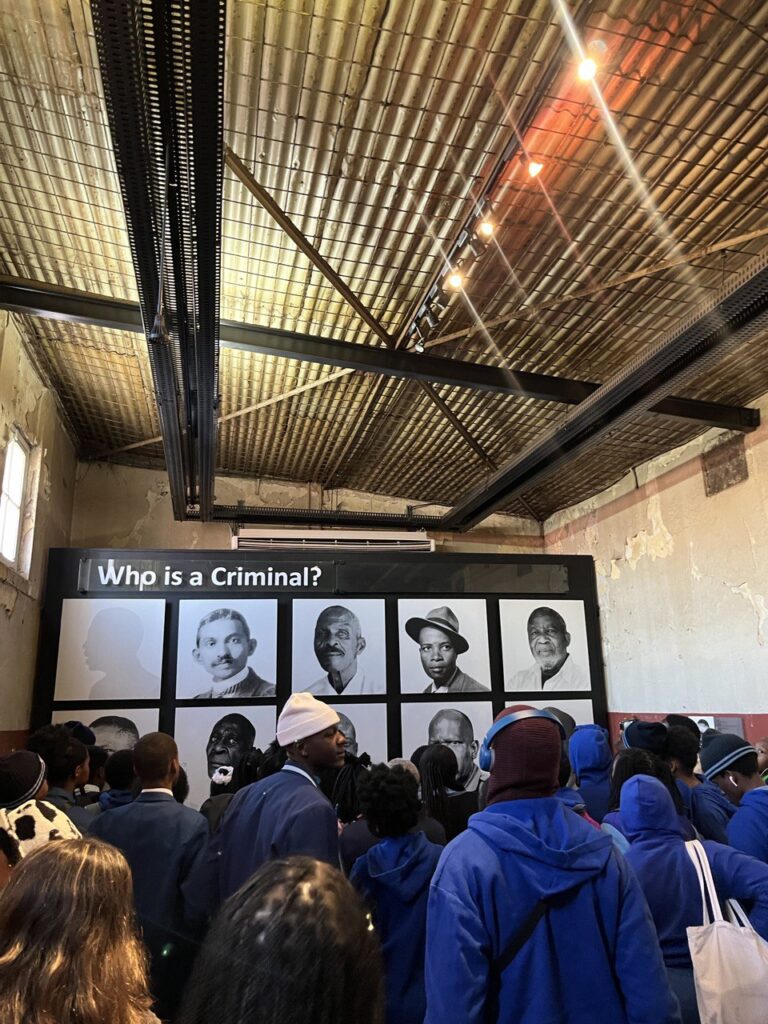

It is kind of ironic how all of our trips to museums and other commemorative locations in Johannesburg as a group of college students have been accompanied by children on their elementary school field trips. They have been lovely company—their stares, giggles and unpredictably hilarious acts were short escapes from the heavy material of the museums. Funnily enough a childhood friend recently reminded me of how I sat on a historical artifact chair that was the seat of Emperor Haile Selassie when we went on a fourth grade field trip to the Addis Ababa Museum. Despite the noise and clamor they create with their bright colored uniforms as they swarm through the exhibits, there is a lot of value in bringing children to these locations. In South Africa, this is especially true because of the important and unique history of children’s involvement in the struggle against apartheid. One of the turning points in this struggle was the Soweto Uprising of 1976 where primary school children went to the streets of Soweto to protest Afrikaans as the language of instruction. The Hector Pieterson Museum is named after and made in commemoration of a 12 year old boy who was murdered along with hundreds of other school children by police who opened fire on peaceful protestors. I feel fortunate to have witnessed school children roaming this museum on the forty-eighth anniversary of the uprising and thirty years since the fall of apartheid.

Although children have limited attention spans and will probably not retain everything the tour guides will explain, museums have a way of shattering the assumption you have as a kid that the world and the rights we enjoy have always been that way. That the fall of apartheid and road to reconciliation were natural courses of history. When giving us a tour of Constitution Hill, the wonderful Lwando Xaso reminded us that, “we did not get here in a vacuum”. We did not get here in a vacuum; we are indebted to countless brave individuals who gathered in groups big and small to agitate for equal rights. I was personally thinking about the civil rights figures in the United States that I admire and how I want to be more intentional about learning their stories and honoring them today. On the other hand I was thinking about the long journey of justice and reconciliation that still awaits victims of genocide and displacement in my homeland, Ethiopia. The Apartheid Museum has taught me about how South Africa came out of apartheid with unshakable resilience and radical reconciliation and I realize once again that they did not get here in a vacuum. There will need to be a lot of work done to forgive and set aside differences but I have a newfound hope that we will get there; forgiveness and unity is not impossible.

On the bus back from the Apartheid Museum, one of my classmates, Ben, shared his experience of having to relinquish the perception of figures like Mandela as superhuman that was shaped by the U.S. education system growing up. I couldn’t agree more about how history is often taught, especially in the U.S. as stories of heroes and villains. Visiting Mandela’s house and the Mandela Exhibit at the Apartheid Museum, I was surprised to see how well these locations humanize an important icon. I learned from the tour guides about the loss of Mandela’s four children and was deeply saddened imagining his grief not just as an important political figure but as a father. There is a world’s difference between seeing an Emperor’s chair or Mandela’s presidential office and visiting Mandela’s one story home in Soweto. I also found that neither the museum exhibit nor Mandela himself shy away from talking about his personal limitations which is rare for most leaders around the world. The exhibit also included many pictures of Mandela in his early life. In the same way that seeing childhood pictures of my parents reminds me that they were once in my shoes, seeing these pictures reminded me that Mandela was once a young man with unique hopes and dreams. I am sure that a lot of other things will shape the school children’s view of Mandela but I think visiting the museum and Mandela’s home plant important seeds in making such an important historical leader more relatable.

Trying to understand what these school children could be thinking about when going through the exhibits had forced me to realize some of my own naive assumptions about history but also helped me appreciate how much my worldview has grown and expanded since I was a kid. I imagine that these school children will grow up to return to these museums. Only at that time, they will stop to read the placards and will take note of the wealth of knowledge that exists in those buildings. Learning about history as a child is invaluable but it also requires constant revisiting and remembering as an adult in order to make room for growth and fresh perspectives.