Being in South Africa has been a wonderful experience. Ignoring that I have gotten to know people from Yale that I wouldn’t have known otherwise, being in South Africa has truly been the most insane reality.

The truth is, I had only been out of the US once before this trip, and that was for a brief one-week stint in Grenada. Besides that, I had been ‘landlocked’ by Canada and Mexico, enjoying my red, white, and blue life.

However, I not only enjoy my Generational African American experience, but I am also committed to it. I have two majors: History of Science, Medicine, and Public Health, and African American Studies. Both are historical in nature. I would describe myself as someone who loves their history, no matter its complicated creation. As a result of my love, my history has wrapped itself so intricately into my future. I have nurtured such a singular interest in the Black American experience that I worried my interest might not align with South African history—that I might enjoy my time here but have little to carry forward.

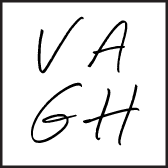

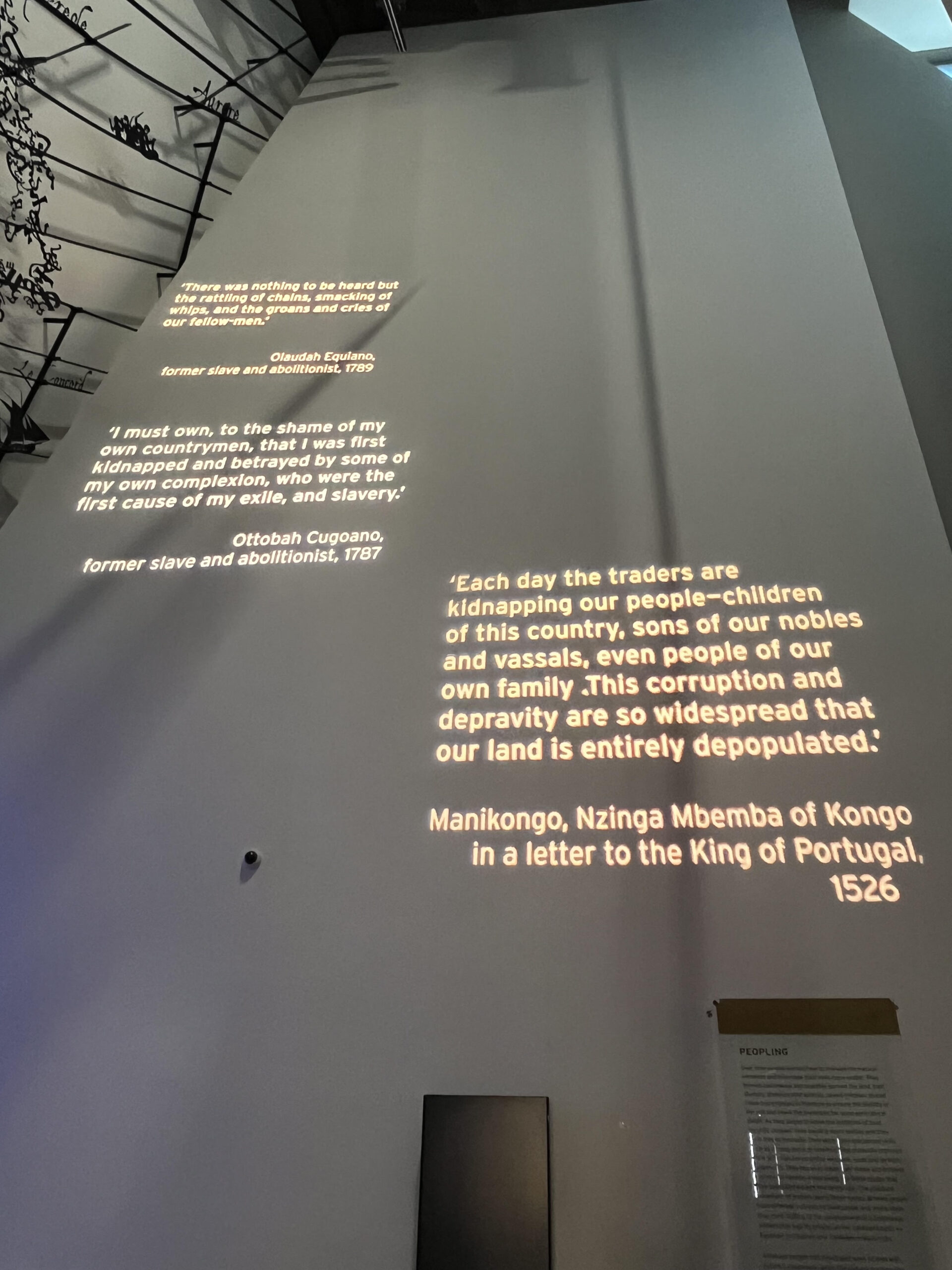

Since being here, we’ve gone to many museums. Which I will say I have enjoyed before but never quite in the way I have here. Here, I have walked through museums, reading each placard and taking the time to let the history sink into me. Though, I worry I may be a bit narcissistic because as I walked through each museum, I couldn’t help but find the ways our histories echoed and intertwined with each other.

The broader history of Africa, predating clear connections to the transatlantic slave trade, has never been of much interest to me. In fact, I subscribed heavily to Stephanie Smallwood, a prominent historian, who wrote in her book “Saltwater Slavery” something to the effect of: the African American began on the boat—in other words, my history begins with the forced disconnection from Africa. So, I honed in on where I began, never thinking about the before. And yet, I have walked into these museums and seen myself in a place I “shouldn’t” exist.

As we toured Nelson Mandela’s house, I cried (though I am an easy crier, so this isn’t of much surprise). Not as they explained his time in jail. Not as I learned the intensity of his call for justice, but when the tour guide explained how Mandela buried the umbilical cords of his children under the tree outside his house. The guide said this was a tradition in South African culture that connected future generations to their land and ancestors. A tradition that placed each child on the long line of “eternal life,” as Tambi, our guide at the Freedom Park museum, explained.

I’m not superstitious, just a little -stitious, as Michael Scott would say. But I couldn’t help but stand there stuck. Left reckoning with the severing of spiritual ties that occurred during the transatlantic slave trade. A spirituality that is so strong and culturally important, I find remnants of its origins generations after its separation. Where might my ancestors have buried their children’s umbilical cords? What language did they think in?

Realistically, my family most likely came from West Africa, not South Africa, yet I still found myself tearing up. What spiritual freedom it is to track 10, 20, 30 generations back. To know more than the last name Beason, which, while I hold close, embodies my family’s severance and forced rebirth.

For me, learning South African history has expanded the limitations of what I can consider mine. As I continue learning the history of South Africa and feel the reverberations of the African diaspora, I am excited to see where else I find myself and even where I don’t.